What the Government Owns & What It Owes

- Jan 20

- 4 min read

Most people know how to read a company’s balance sheet. Very few realise that the Government of India also publishes one. Maybe, not as a headline number. But as a structured statement of assets, liabilities, and net position.

This post is about introducing that balance sheet, and making it intuitive.

India Has a Balance Sheet Too.

At its simplest, India’s balance sheet answers one question.

What does the government own, and what does it owe?

Just like a company, the balance sheet is split into:

Assets - where past spending has accumulated

Liabilities - how that spending was financed

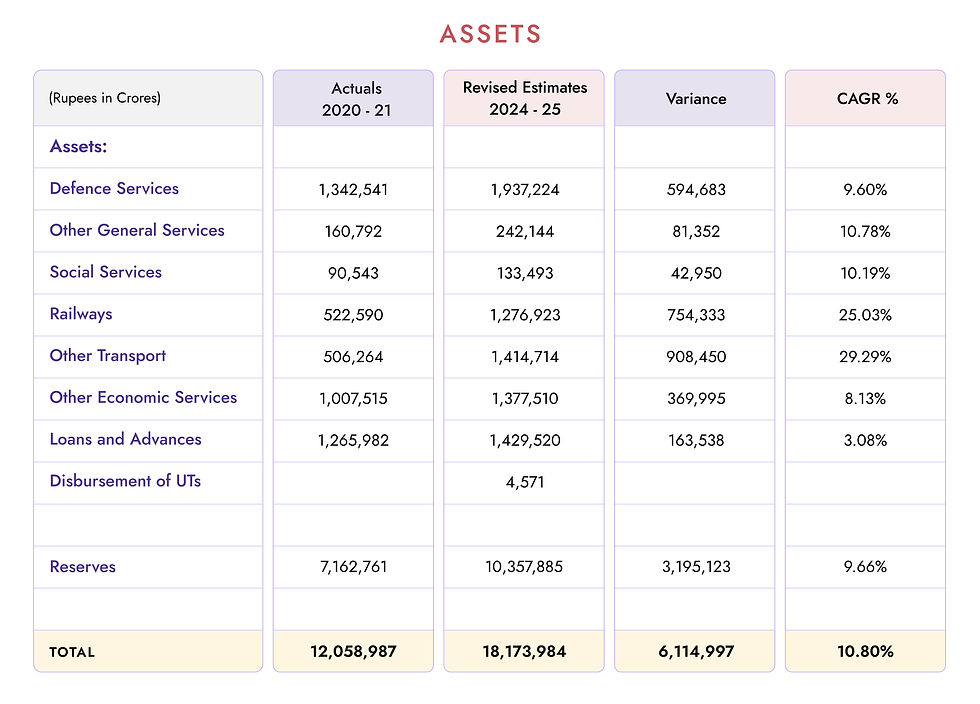

Between FY 2020-21 and FY 2024-25, India’s balance sheet expanded meaningfully, but not uniformly.

The Asset Side: Where Public Money Has Accumulated

1. Economic and Physical Assets: Revenue-Generating and Growth-Enabling

The largest asset blocks on India’s balance sheet sit in:

Transport infrastructure (railways and other transport services)

Defence services

Economic and social services

Unlike purely administrative assets, many of these generate revenues in isolation:

Railways earn freight and passenger revenues

Roads generate toll and usage-linked receipts

Economic services recover fees, charges, and user payments

At the same time, their importance extends well beyond these direct cash flows. These assets also:

Lower logistics costs

Improve productivity

Enable trade and mobility

Expand the formal economy

Which, in turn, raises GDP and broadens the tax base. In corporate terms, these assets function like core operating assets that generate revenues directly and enable the rest of the business to scale.

So while their direct revenues may not always cover full capital costs, they play a dual role: a) Earning income on their own and b)Supporting higher government revenues over time through economic expansion. This is why sustained investment in economic assets continues to shape both sides of the government’s balance sheet.

Economic assets earn revenues directly and, more importantly, expand the economy that sustains government revenues over time.

2. Loans and Advances: The Government as a Lender

A significant portion of assets appears under Loans and Advances.

These include loans to:

State governments and Union Territories

Public sector enterprises

Foreign governments and international bodies

Other long-term investments and recoverables

For a company, this would resemble inter-corporate loans or strategic investments.

They are assets on paper, but Illiquid, long-dated, often policy-driven rather than return-driven. They strengthen the system, not the treasury.

3. Reserves: What the Asset Side Is Really Recording

Reserves on the government’s balance sheet require a different lens from corporate accounting. In a company, Reserves usually reflect accumulated profits. On the Government of India’s balance sheet, Reserves on the asset side effectively reflect accumulated fiscal deficits, that is, losses funded by borrowing year after year.

In other words, they record the net impact of spending exceeding revenues over time, financed through debt. This is not an anomaly. It is how sovereign accounting captures long-term fiscal outcomes.

Why This Isn’t Necessarily a Red Flag

For readers familiar with growing organisations, the parallel is intuitive. A fast-growing company may:

Invest heavily ahead of revenues

Run accounting losses for years

Accumulate deficits funded by debt or equity

Yet still create long-term value, if those investments expand future earning capacity. Similarly, government reserves need to be interpreted alongside asset creation, GDP growth and Revenue expansion over time.

The key question is not whether accumulated deficits exist, but whether they are accompanied by rising economic capacity. That is why reserves make sense only when read together with the asset mix, not in isolation.

The Liability Side: What the Government Owes

The liability side is where the balance sheet becomes more intuitive, and more instructive.

1. Internal Debt: The Backbone of Government Financing

The largest liability is internal debt, raised primarily through government securities, treasury bills, borrowings from domestic financial institutions. This is similar to a company raising long-term bonds and term loans from the domestic market.

Internal debt dominates because:

It is raised in local currency

It reduces exposure to external shocks

It can be rolled over across generations

This is deliberate design, not an accident.

2. External Debt: Present, but Contained

External debt forms a much smaller share of total liabilities. It typically arises from multilateral and bilateral borrowings, external assistance for specific projects. From a risk perspective, its scale is modest, its growth is gradual.

In corporate terms, this is foreign currency borrowing, useful, but carefully limited.

3. Other Liabilities: The Quiet Obligations

These include amounts payable by the government towards:

Provident funds

Small savings schemes

Deposits and savings instruments

Various statutory and trust obligations

For a company, this would resemble, employee benefit obligations, customer deposits, and deferred payables.

They are not market borrowings. But they are real claims on the system and must be honoured over time. The fact that this line item does not grow aggressively is as important as its absolute size.

Putting Assets and Liabilities Together

Seen together, India’s balance sheet reflects a familiar structure:

Long-lived, service-oriented assets

Debt-funded expansion

Deferred obligations to savers and employees

Limited liquid buffers

This is not excess. It is how large, enduring organisations operate. The key question is not whether the balance sheet has grown, but whether assets and earning capacity have grown alongside liabilities. That is where debt servicing comes in.

Why the Balance Sheet Matters Before We Talk About Debt

The balance sheet explains why debt exists. Borrowing has not funded consumption alone.

It has funded:

Transport networks

Defence capacity

Social and economic infrastructure

Support to states and public enterprises

Debt, in this context, is not a red flag. It is a financing choice. Whether it remains sustainable depends on revenue growth, interest costs and economic expansion.

A balance sheet does not argue for or against policy. It simply records the consequences of choices made over time.

* Disclaimer *

This article represents the author’s personal analysis and interpretation of publicly available budget data. The views expressed are for informational and educational purposes only and do not constitute financial, investment, legal, or policy advice.

No responsibility or liability is accepted for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this content.

Resources & Data Reference:

Annual Financial Statements and Receipt Budget of the Government of India (FY 2020-21 to FY 2024-25), including the Assets and Liabilities Statements.

Budget documents as presented to Parliament.

Aggregations and CAGR calculations performed by the author for analytical purposes.

Comments